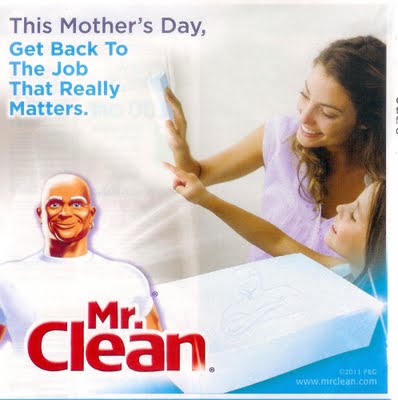

I love TV commercials. As a 12-year-old, I used to mansplain the gender dynamics of Mr. Clean ads to my brother, my captive audience of one, as we waited for Daria to come back after a word from her sponsors. Commercials are a 30-second tap of the Zeitgeist. They need you to buy and they have limited time to convince you to do it, so they get right in the vein.

Usually, there’s enough going on in the world, enough variety to our lives (and in the resources of ad makers) so that I can find an assortment of horrifying standards, goals and obfuscations to rant about. But right now, exactly two things are going on in the world, and one of them is too polarizing to base primetime TV commercials on. (It’s hard to even make sure BLM journalism is paid). In case you missed it, the other thing going on is the Corona Virus. It’s why you can’t leave your apartment, why my father’s repertoire of ‘peace in the house’ related catch phrases is on loop and why every TV ad now looks the same. It’s a vulnerable time, and we’re all understandably quite frightened. Most of us feel locked in. Many of us have lost our jobs, our sense of control, our sense of future. That’s why when Lexus promised me freedom in The Road Ahead, I nearly leapt off the couch in analytic glee.

Commercials sell us things, but more often they sell us versions of ourselves. Car ads are no different. Actually, car ads are farcically obvious in this regard, and thus tend to fall into three types: the exemplary object, the metropolitan exception and the American conqueror – let freedom ring.

The first is selling you a product as the product. They assume what you want in a car: it’s affordable; it’s well-made; it’s a sexy, innovative, technological marvel. This is where you get the ultimate driving machine, fetishizing shots that turn the car into the attractive model and dissect her into perfect parts for your personal purchase. This is where you get things like Honda’s automotive Rube Goldberg homage.

The metropolitan exception are all those ads with slick driving on city streets. They usually contain some warning to the effect of not trying this at home, professional drivers, yada yada yada. These might be professional drivers in the commercials, but if you buy this car you too can rise above the riff raff of your city. You can be of the metropole but not in it. Or in it but not of it. (Whatever order of prepositions means that you know things but you’re better than your peers). You’re special; you’re the jungle king, the traffic guru, the only one able to out-maneuver any daily obstacles before which lesser men would crumble. In these instances, you’re not buying a car, you’re buying a self.

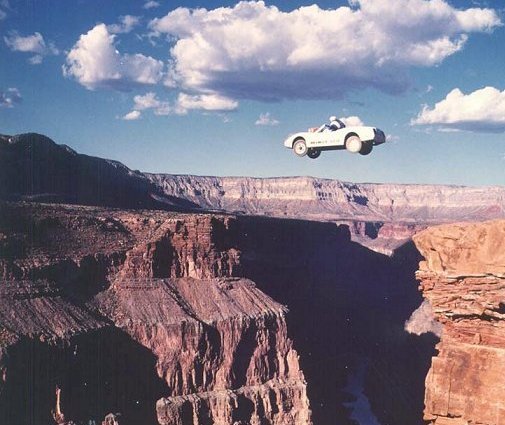

The last, the American conqueror, is by far my favorite because it hits all my buttons: nationalism, masculinity and orgiastic shots of the US landscape that reinforce the American narrative in the form of occupation and consumerism. You’ve seen plenty of these. A car winds by itself down Highway 1. Now a POV shot: you’re in the driver’s seat as waves crash impossibly outside. It switches back to a shot of the car. Blessed, blessed drones. Now we can watch this beautiful machine kick up desert dust. This Lexus commercial, that promises us “The Road Ahead” as uncertainty and crumbling US hegemony rattle the hearts of every citizen, is no different.

At first blush (and for those of you who feel no need to break down every cultural artifact into its constituent parts, societal histories and potential consequences) this ad seems to be a reminder of hope. It asks “Of all the places you’re looking forward to, where will you go first?” It’s like, hey there frustrated consumer stuck on your couch with an overwhelming sense of being trapped and powerless and very little idea of what comes next or really if next will ever come, there’s a whole world out there and you will have access to it again. As is your right as a warm blooded American, goddamnit.

But really, why do I see nationalism here? A nation is a people who share time and space. More specifically, they share a history and a place. American national narratives cannot base their claims to the place part of this equation on some notion of autochthonous belonging. We’re a settler society. In the least horrifying versions, we came here as immigrants. At its most euphemistic, we found this land. But really, we took it. Manifest destiny, bitch.

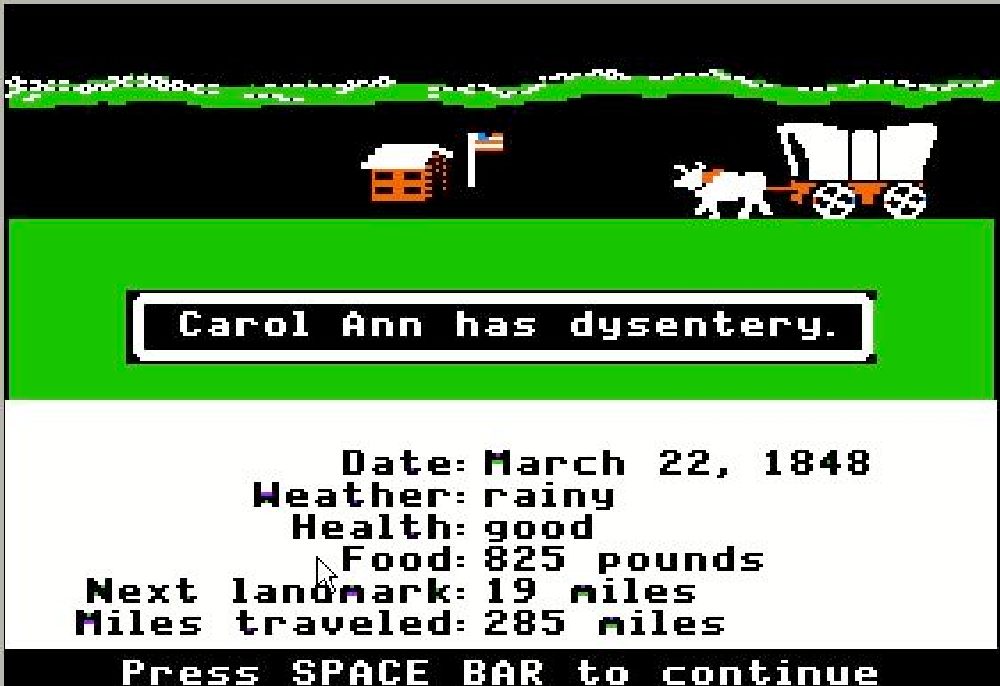

Americanness, in its majesty and monstrosity, is founded on a narrative of conquest. One wrought with blades and blood, with diseases, with despots selling land that wasn’t theirs and canoes led by unwilling guides. We took this country with wagon wheels and brave trailblazers. Making major roads is always a militaristic proposition. Yes, they have other uses, but if you think Eisenhower pushed for 90% federal funding for the building of the interstate highway system so that lawyers could commute from Connecticut instead of living on the Upper East Side, you’re overestimating the importance we place on people who push paper in the name of the law. (Eisenhower had been jonesing for a more comprehensive system since his 64 days in 1919 with the Transcontinental Motor Convoy and his WWII years with the Autobahn.)

The use of roads in modern colonization illustrates their relationship to conquest perfectly. In places like Hawaii and the Philippines, roads moved our troops, facilitated extraction of raw materials and –literally and figuratively– turned these landscapes (and the people in them) into objects for our enjoyment. Consumption is a type of conquest. Even watered down to tourism or the Sunday drive, sightseeing is still an act of surveillance and power. While we’re enjoying the majesty of a beautiful place and may feel humbled in its presence (because oh my god, have you seen our national parks), we also get our rocks off from our ability to invade it, observe it and dominate it.

Even before the invention of cars, popular discourse framed the Americas as a virgin land, ripe with bounty and begging for (male) civilizing conquest. Car commercials have long echoed this romantic narrative of entry and discovery in the feminized landscape. Consider the now nostalgic postcards that are Chevy’s ad series from the late 1940s and early 1950s: Roads to Romance.

Don’t even get me started on the opening shots entering the “deep rocky folds” of the canyon.

But, don’t forget: roads, like cars, are the fetishized instrument of this entry. I think of the Pennsylvania Turnpike as a roadway to be avoided at all costs. But at one point, it was framed as a lengthy, throbbing byway.

For all my bellowing about narratives of masculine hegemony being foisted on us through the metaphor of cars and highways, that cars are sold to us by appealing to a romanticized vision of violent, consumerist conquest, I also find the idea of Americanness these ads capitalize on to have a hopeful aspect. As we all sit in our homes, camaraderie mediated by screens, events attended via zoom, closeness with others reduced to a voice on the other end of the line, these commercials somehow remind me that we will be citizens again. We lay claim to the land by inhabiting it, by letting it inhabit us. Traveling in the US is a way of witnessing, a way of inscribing ourselves into our place, our history.

I do not wish to obfuscate that these commercials are deeply problematic for a variety of reasons (or my mixed feelings about the above Volvo S90 commercial that stuffs Walt Whitman into Josh Brolin’s extremely alluring proto-male voice in order to back drop the wet dream of every hipster I spent college hating and lusting after). Lexus’s new commercial, The Road Ahead, with its shots of our waiting virgin landscapes and our muscular highways, is a promise not just that we’ll be able to get out of our houses again but that we’ll soon get our American mojo back, that our romantic adventure story with the land will continue. Lexus will welcome us back.

As always – loved reading!

I love the irony that the poetry of Walt Whitman– who toed the boundaries of sexuality– was used to depict the open road in a hetero-masculine light.

Walt Whitman continues to be progressive by showing us that masculinity need not be confined to cowboys and lone rangers and truckers. We can be overwhelmed with emotion, awed by nature, or crippled by the multitudinous presence of other people without being pigeonholed into one sexual category or another. Hearing his words over that Volvo ad is as strange and contradictory as hearing, say, Mare Kondo’s.