“Beetlejuice. Beetlejuice. Beetlejuice!”

Damn it. I’m still sitting in this room by myself. I was hoping Michael Keaton would appear from a sudden bubble of mist. I always thought Beetlejuice would make a good drinking buddy. Or the one that finally gets you killed. It is a show about death after all.

Generally, by saying the name three times you conjure him into being, or, more accurately, drag him over the line into our world. An idea, a runaway desire, gets pulled from the dreamy side beyond into our reality simply by being articulated. This describes any creation and certainly applies to the creations that are adaptations. An adaptation begins with a reading. When you read, characters and places from the page, swell in your head, take on new proportions, root themselves as ethereal wisps and grow branches in the particular soil that is your imagination. That’s why we always whine that the movie wasn’t as good as the book. The story’s lost the skin that made it yours, loosed a bit from the infinite space in your mind where it evolved. That and because the book came first. So, any adulterations are of the urtext, and furthermore, your personal urtext. Also, because Hermione was supposed to be black.

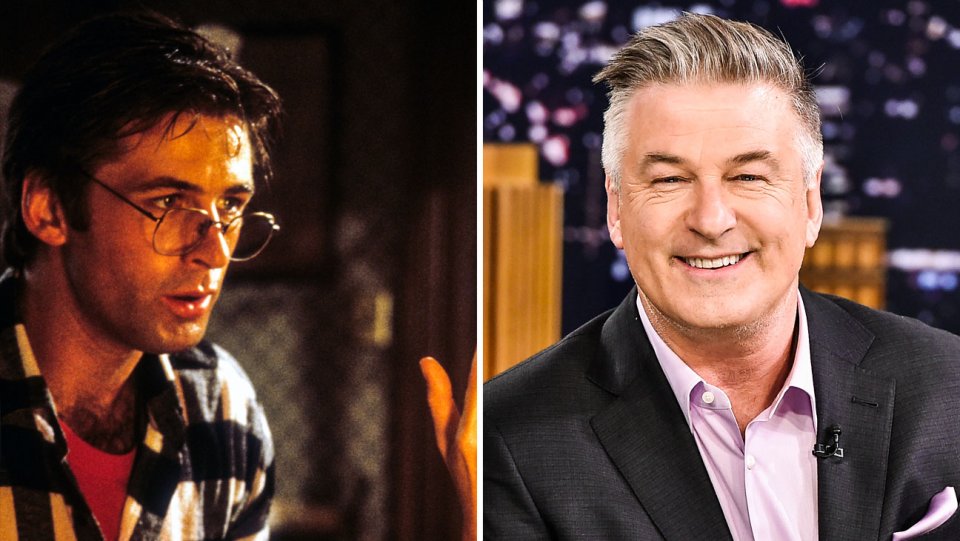

But, adaptations are also a brave gift. An author shares their reading, which even in the more fixable cases of a filmic source, still varies from watcher to watcher. The reader/adapter opens himself to the doubly cruel criticism heaped on him as author and adulterer. In one sense, adaptations offer a digestion of elements. Such and such themes are present. These characters are motivated by X; those by Y. Did you, first of all, remember that Beetlejuice is about death? I watched the 1988 marvel as a goth girl’s surreal and angsty dream. Her marriage of who she was with a productive and peaceful way of being in the world. I saw the comment on the potential banality of the other side, laughed with the hilarity that the end of my days might be punctuated by waiting rooms and Kafkian bureaucracy. I took a comfortable and delighted umbrage that in the end, my end could be both sublime and ridiculous, but with any luck it would be clothed in the striped fantasy of Tim Burton. I also watched it for the occasional raunchy joke, Alec Baldwin’s once very sexy pout and the fact that Gina Davis still looked inexplicably gorgeous in the worst housedress the 1980s had to offer. The fact that it was about death and mourning was far from my mind.

I’ve since seen the movie many times. My readings have developed somewhat but nothing to uproot a general feeling of loving nostalgia. Reaching adulthood cleared my eyes to the miracle that is Catherine O’Hara and lessened slightly my distaste for Beetlejuice’s green rimmed face, but no major changes affected my initial reading of the movie. But, Eddie Perfect, Scott Brown and Anthony King’s musical adaptation revealed aspects I didn’t catch in the original and expanded others it might have been nice to see more of.

First of all, it’s a movie about death and transitions, about gruesome ends over covered bridges (or through the floorboards of creaky houses), about what happens to us when we die, about what happens when those we love pass away. (It’s also about the figurative death that is moving to Connecticut). How did I never notice before that Lydia Deetz loses her mother and is faced with the daunting demand of mourning this death while her father just wants to move on? Such a theme becomes incredibly, if not cloyingly, obvious in the musical adaptation with a song like “Dead Mom.” The Maitland’s desire for a child is present in the film, but the play opens with Adam polishing a cradle and gives way to a song and dance number about failed hobbies, life goals and a host of other “Ready, Set, Not Yets.” (If you don’t get it in the first act, the second act has a song called “Children We Didn’t Have.”) I didn’t notice the comment on the 1980s economic boom that sent city slickers to the suburbs with their supposedly superior tastes or grasp the creepy child bride vibes of Beetlejuice trying to marry Lydia until I saw these things again in musical version, updated to 2019 and belted out in song. (I might have missed the last one because I was distracted by Winona Ryder wearing her weight in red tulle).

Different media can bring out different things. Musicals are a genre in which characters sing about their feelings…or delay the action to repeat over and over what just occurred. (Thanks, Tony. We got it. You just met a girl named Maria. Yeah we saw that. It literally just happened. Wait, what was her name? Oh, Maria. Thanks.). So it’s not shocking that Tim Burton’s film does not include long digressions in which characters reflect on their own psychological processes, but the musical can look straight out at the audience and say that people have trouble talking about death, repeat that yes, by people they mean you, and then force you into an uproarious two plus hours of talking about it. The update – fast forward 30 years – also underlines certain themes that though in new clothes, still persist. The 2019 vanilla Maitlands are marked by Pottery Barn and failed hobbies like brewing kombucha instead of loudly boring sartorial choices and a station wagon. Delia Deetz is a life coach instead of a bad sculptor, but the types are the same.

With updates, new media and the particular twist of a particular reader, adaptations can also expand things that weren’t there before at all. For example, in the 1988 filmic version, Lydia does not jump into the underworld to be followed by her father who finally sees his daughter’s suffering and has decided to engage with his feelings in a public and vulnerable way. Thank you Broadway, thank you 2019, thank you adapter. Or not. Perhaps you preferred that Daddy Deetz is kind of dim. (Perhaps I do too). But, like it or not, the adapter pays homage and takes flight. I applaud the effort. A standing ovation.