God I love I steampunk (not in a creepy cosplay way…although, some of these outfits). I loved Carnival Row. I need to tell you this now before its ads vanish from my Instagram feed and the show becomes irrelevant and I’m forced to admit that really, it was only sort of tepidly good and that though prognosis looks positive for the making of a second season, likely that season will be closer to outright bad.

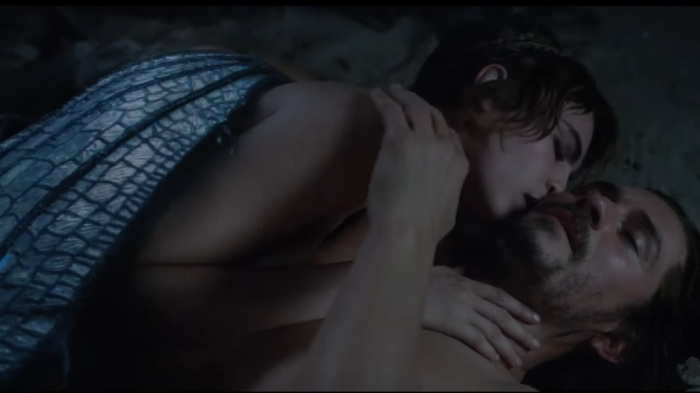

Sad but true because a, most of the things I was waiting for already happened (ie: the bangathon) and b, they killed off the best actors in the show (oops, spoilers). In the meantime, I got to enjoy all my favorite things. Multiple romantic plots, magical creatures, odd inventions, a protagonist with a past that’s a mystery even to himself, and Orlando Bloom showing signs of aging into the man-meat version of a fine wine. Sign me the F up. Steampunk with fairies and a for-mature-audiences-only rating. Absolutely. But, I think I love the show even more for what it highlights about the genre, for an oblique and accidental awareness of an insidious vein hidden in steampunk, a vein we’d deny if we looked at it directly but which we celebrate with mythic yearning.

Sci-fi fantasy with 19th century aesthetics, steampunk is a nostalgic jaunt full of gritty hope. It paints the Victorian period as a time of dark-hued optimism, full of mystery and possibility, inventions and grimy, grimy authenticity. It has its cake and eats it too. There’s still magic, but a magic waiting for discovery, as a place of intellectual conquest. Scientific conquest. Actually herein lies the rub: conquest. Because the line between the scientific kind and the imperial kind is, in fact, more of a loop.

Carnival Row covers life in the Burgue, a fictional city in a fantasy land that’s really a cipher for London in the Victorian period if, as one critic put it, “the great European powers established colonies and fought proxy wars in the realms of the fae rather than in India or Africa.” It bobs and weaves through various interconnected plots that take us through the hot topics of immigrants in an empire’s capital, interracial (in the show, interspecies) relationships, palace intrigue in a parliamentary democracy and murder most foul. Rycroft Philostrate (Orlando Bloom, whose real last name suits him more than this ‘lover of battle’ crap), a former soldier in the fae lands, is now a police detective in his hometown. He investigates a string of murders while pining for his lost love, Vignette Stonemoss (Clara Delevingne), a scrappy warrior and fae librarian. (Yes, the ridiculous names continue. Prosaic versions of Midsummer Night’s Dream characters abound, and the cast reads like the fairyland forest of the play and its ordered Athens finally came together. C’mon, Imogen Spurnrose? Jonah Breakspear? Where is Peaseblossom?). The lost lover arrives in the Burgue after her freedom-fighting-cum-human-smuggling has ended in naught. Vignette winds up another refugee, bouncing from indentured servitude to black market criminality (she’s not suited to prostitution, as her friend Tourmaline is). She contends with longing for a country to which she cannot return because it’s occupied by a rival imperial power (rival to the Burgue, not to her own people; they are merely casualties in a battle between a hero and an enemy). Existential sadness and the navigation of a system designed to keep her powerless.

Her plight sound familiar? It should. It sounds particularly familiar to me here in the US as we watch immigration politics take an unabashedly dystopian turn.

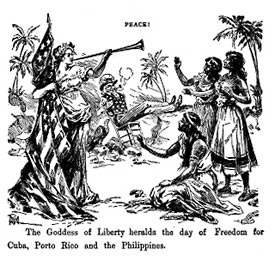

But, I digress. (Though not really, if you think about it). It also sounds like Victorian England, the period that retrospectively glows with the gritty optimism of the Second Industrial Revolution and the consolidation of the always-sunny British Empire. The branch of soaring science that brought us to new heights of what we could do and know shares a limb with the penetration of foreign geographies and the horrors faced by those who came from there. Enter Edward Said’s Orientalism. Yes, it’s a throwback. Who needs a lesson in colonialism written in 1978? Well, Travis Beacham’s story is giving us one in both obvious and subtle strokes.

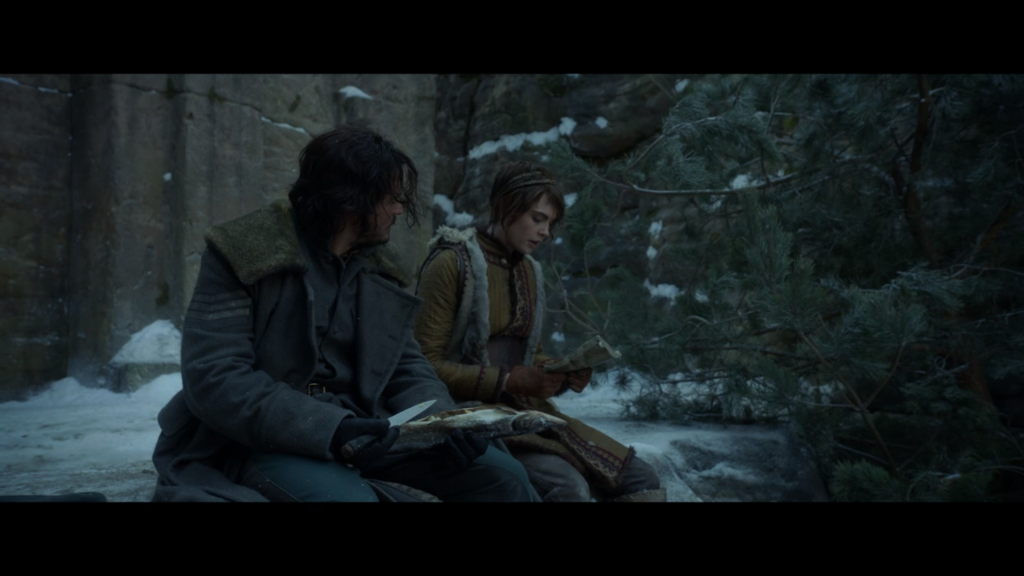

The show knows it’s addressing invasion. In a moment of nearly comic self-awareness, Rycroft and Vignette sit outside the library in her city and discuss his favorite book, the one that brings the two lovers together. She (theoretically like us) is forced to reevaluate what the fiction is aiming to be, saying “At first it seems to be a droll and colonialist fantasy.” Rycroft finishes her thought: “Valiant human explorer romances some native princess.” Don’t get me wrong. This is exactly the story you’re watching. It’s a story much loved during the period the show is aping and remains a compelling plot. But there’s a twist, a subversion. The native princess and the valiant human have a baby, and that’s the narrator. An exact parallel of make-my-knees-buckle Bloom’s situation. She (in the book) and he (in the TV show) spend their lives passing, hybrid children searching, forever inbetween, their truth unwelcome anywhere. This is some broad strokes unexamined colonialism is very, very bad kind of stuff. This is also the moment that Carnival Row really had me. If you can go meta and pose the question of how fiction participates in oppressing people at the same time, your hand may be heavy, but it’s also quite deft.

So what about the subtle? Why am I mentioning Mr. Said (if not just to give myself an excuse to reread theory and posture to my eight readers about doing so)? Carnival Row also gets at how science, study and even romantic fiction were part of colonial conquest. It reminds me that when we go all swoony for these mind-blowing inventions, for this brave new world and the people in it, and even more so because they’re set in a nostalgic moment, we are also hero-worshipping a rather dark conjunction of events.

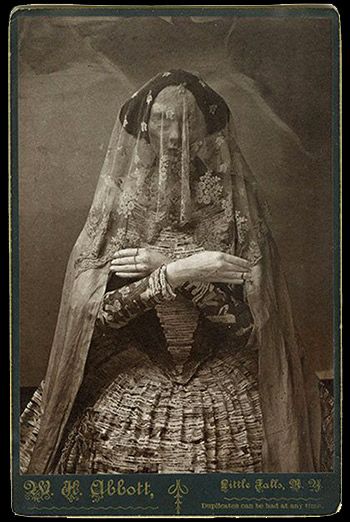

“Orientalism,” the study of the “Orient,” aka all lands East of central Europe, is an academic tradition that began before the Victorian period. Its experts and aficionados were linguists, historians, geographers, biologists, travelers and readers of novels. In their study, the “Orient” is object; the learned man is subject. As Said says “the Orient is all absence, whereas one feels the Orientalist and what he says as presence.” Turning the “Orient” into an object of study facilitates invasion because it turns “orientals” into objects. Being an object robs you of your ability to self-define. Actually, it silences you entirely; it makes you absence. You are something in a petri dish, a case study, a museum object, an exotic character in a novel or a brothel. At best, you are a crone-carrier of ancient (read: backward, yet magical) wisdom. Further, Darwinism adds categories of developed and under-developed, which are quickly applied to peoples, vindicating a Western “responsibility” to “care” for “lesser” peoples. Hence all that coming to the rescue in new lands. Should you remain unconvinced at the connection between a new value placed on scientific study and imperial invasion, consider one professor’s early 20th century bid for the creation of a school of Oriental studies in London based on the grounds that such a thing was “a great Imperial obligation,” “the necessary furniture of Empire.”

This, my magical friends, is why little Vignette is so enraged to find her library moved to a London museum and her access restricted by a rule that does not allow unaccompanied fae. (Though the story also makes it about her love of Philo with intercuts of their relationship, lest we forget our loins and heartstrings while watching). The show picks up this theme of scientific study and imperialism most beautifully in the opening credits, which feature all the creatures, but none as living beings. They look like the artifacts in a museum, suspended, measured and behind glass. They move only when inserted into an invention of the time, their photographs spun into a moving centaur. There is a living girl there, presumably a girl of the Burgue. Her reflection blinks in the glass as she tries to touch some immobile creature.

When we watch these things, we know a little more, and we know a little better. Carnival Row plays with that idea. It questions a nostalgic orientalism we’ve preserved and placed into a fantasy of grit and steam and magic and scientific optimism. Perhaps the show works like the hybrid child, struggling with how much truth it asks others to see yet still fluttering with stylized beauty. Perhaps this is the part that makes it punk. It follows the hidden other, the struggling underdog who may eventually undo the system. Ok, I take it back. Bring on season 2. I want more.