In January, one of the best shows on TV will die. It lived a good life. It committed no grave sins. It didn’t stay past its expiration date. It did the best it could, as we’re all instructed to do, and son-of-a-bench, no bullshirt, it did a forking good job. NBC’s The Good Place deserves to go to the Good Place. Hopefully, that’s where it will endure in our minds, for memory is the one space we’re certain there’s an afterlife. Otherwise, we have no forking clue.

We imagine a majesty with that mystery. We anticipate soaring, cosmic justice that will answer life’s ultimate queries. Something that will make all this have made sense, something otherworldly that suits the momentous occasion that is the end of our incredibly important lives while simultaneously bestowing logic on all the seemingly random, seemingly meaningless flailing around we did on earth. We imagine that the hereafter will shed light on the before and right its wrongs. Structures will be revealed. Every sinner and sinned will get their just desserts and the terms will be so exaggerated as to be unmistakable.

Dante’s Inferno is thus harrowing but reassuring. It corroborates a certain hierarchy of values that bears some relation to what we know. Ok, nine circles of Hell is somewhat ornate (maybe Mr. Alighieri could have combined a few: gluttony with greed, wrath with violence), but through this extreme organization, we know lust is not awesome (second circle) but treachery’s much worse (ninth circle). In the former, lovers swirl about in a terrible storm, not unlike the tempests they wrought on themselves and others while up top. In the latter, traitors are varying degrees of stuck in a frozen lake, for “only the remorseless dead center of the ice will serve to express their natures. As they denied God’s love, so are they furthest removed from the light and warmth of His Sun. As they denied all human ties, so are they bound only by the unyielding ice” (Canto XXXII)). There are crimes and there are punishments. There is justice; it corresponds with what we know, but it’s spectacular, confirming the wisdom, presence and divinity of its architect.

But what if dying is, like everything else, a rather more banal affair ruled by some of the least majestic, most individuality effacing parts of being alive? What if death reveals that there was a logic behind everything, and it’s just as impenetrable, faulty and boring as the one you knew? What if death is office life?

That would be hilarious.

I giggle my head off when Rowan Atkinson welcomes me to Hell, clipboard in hand, as Toby the devil. I find a risible sense in the reaping of souls via post its in Dead Like Me. I rock with resigned laughter as Adam and Barbara don’t yet know of Beetlejuice, so they sit in the waiting room, tour through bad filing systems and try to extract assistance from their overburdened caseworker. It’s the ridiculous in the sublime, but it’s also the cosmic joke that life after death has the same structure as death in life.

Two recent (and frankly fabulous) shows, The Good Place (2016-2020) and Miracle Workers (2019-), build their comic genius from this starting point. What is humor but an abrupt change of orders? A quick jab at your expectations? A sudden change in perspective? One that perhaps throws in stark relief something we’ve known all along? Humor, like death (we hope), tells us a secret and offers a balm (assuming we’re on the same side of the joke as the teller). These series do not show us what comes with death, but they express frustrations that we feel in life, as does, honestly, Dante’s Inferno. Though it tells us of some faith in God, it reflects more about earthly hierarchies than it does divine ones. (Consider that 21 centuries before and across the Ionian Sea, Odysseus was the hero; Dante puts him in the eighth circle of Hell for fraud).

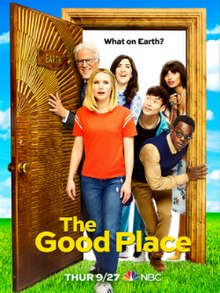

The Good Place and Miracle Workers are afterlives of bureaucracy. Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristen Bell) wakes up to her death in a waiting room, whence she proceeds into an office to get the results of the test that was her life. Michael and Shawn (two demons played by Ted Danson and Marc Evan Jackson) engage in petty office politics, the latter of whom often appears leading team meetings or presenting training and success data at company-wide events. Miracle Workers capitalizes on similar gags, placing the action in the halls of Heaven Inc., the failing company that runs Earth. Eliza (Geraldine Viswanathan) is transferred to the Department of Answered Prayers where the only employee is Craig (Daniel Radcliffe in full pasty glory). The action, and maybe the Earth, explode when Eliza gums up the works by bringing glaringly obvious problems to the boss’s attention.

The idea that these shows are more about this life than the next is not new. Their send up of office life makes this abundantly clear. But, dragging the majestic down to the level of the quotidian ultimately speaks of a profound loss of faith in structures we once found reassuring, true and worthy of veneration. This as much a question of our feelings about the divine – or the divine plan – as it is about our outlooks on all of our systems. The systems in these shows are broken. In Miracle Workers, Heaven Inc. is basically unhelmed. God (played by the brilliantly cast Steve Buscemi) is an illiterate, narcissistic buffoon. He seems dejected at the pain and chaos of the world he’s created but does nothing to correct it. The last season of The Good Place is dedicated to four formerly mediocre humans and one demon trying to prove that the parameters that decide who goes up and who goes down no longer work for the world as it is. The group running the actual good place writes strongly worded letters and forms ineffectual committees. The god-figure in this show (also brilliantly cast with Maya Rudolph) is an indifferent, television addicted judge, black robes and all.

In both shows, the people must turn to one another, for the higher powers are incapable of helping. The help they do offer, once they’re finally convinced of its need, is to scrap humanity and start over. Discovering that their agitation for improvements results in their imminent demise, the people rely even more on one another as they attempt to fool the gods into not annihilating them. They’re in the moral right, they’ve put in the time and done the hard work, but the outlook is bleak. We have no idea what’s next. So, we laugh, at the absurdity, because that’s part of how we keep trying, how we place our faith in one another while the divine judge, the CEO is off somewhere catching up on TV.