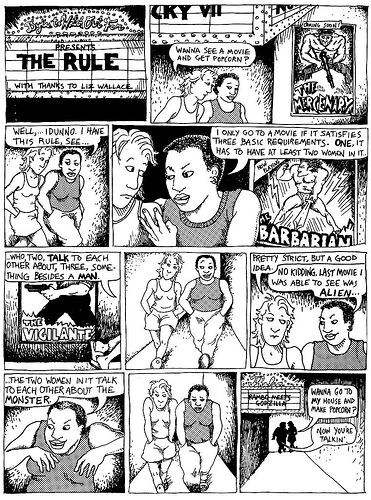

The Bechdel Test is laid out very simply. For those of you who don’t know it, there’s a whole website that explains, but basically it’s three rules that actually fit into one sentence: There are two or more female characters with names (1), who talk to each other (2), about something other than a man (3). That doesn’t seem that hard. That happens to me every day, even if just me calling my mom to talk about myself. But, as any explanation quickly makes clear, precious few movies make it into this category.

The Bechdel Test is laid out very simply. For those of you who don’t know it, there’s a whole website that explains, but basically it’s three rules that actually fit into one sentence: There are two or more female characters with names (1), who talk to each other (2), about something other than a man (3). That doesn’t seem that hard. That happens to me every day, even if just me calling my mom to talk about myself. But, as any explanation quickly makes clear, precious few movies make it into this category.

Reciting the Mahabarata would take less time than reading a list of the mainstream films that fail this test. (In case you wanted to hear that, at least a condensed version).

In the 1985 comic, the test appears almost as a joke, but one whose laugh quickly trails into a disgusted, powerless sigh. The women decide to go home and make popcorn, in Bechdel’s story, because the prospect of another movie with flat female characters and non-existent feminine relationships frankly sounds boring. Bechdel is about representation, and what it calls out are the very limited roles of women. Oh, not so limited. In the movies, they can be wives, mothers, sisters, witches, bitches, dreamgirls and an occasional sympathetic fat friend. They can be all these things as long as they don’t exceed their functions of rotating around the bright center of the Copernican universe: some dude. What the Bechdel test is signalling is that a vast majority of popular movies limit women to the status of objects, plot devices or symbols. Even the sympathetic ugly friend graced with an ounce of emotional complexity is merely a man mirror. She’s there so he can see himself or so we can see him in a different light, so we can say, “oh look, he’s not a completely self-involved, vapid POS; he has an unattractive female friend.” (Except that he is, and honestly, we’d be upset if he hooked up with the fat chick.) The takeaway is that only men can be real people. Women are accessories, tools, and only have value in terms of what they mean for men. The very fabric of society depends on it (Levi-Strauss is just reading the rules). What the Bechdel test exposes is that in representations of society, women cannot exceed their roles as objects and cannot, cannot, cannot be allowed to form their own bonds…unless they’re over men.

In the 1985 comic, the test appears almost as a joke, but one whose laugh quickly trails into a disgusted, powerless sigh. The women decide to go home and make popcorn, in Bechdel’s story, because the prospect of another movie with flat female characters and non-existent feminine relationships frankly sounds boring. Bechdel is about representation, and what it calls out are the very limited roles of women. Oh, not so limited. In the movies, they can be wives, mothers, sisters, witches, bitches, dreamgirls and an occasional sympathetic fat friend. They can be all these things as long as they don’t exceed their functions of rotating around the bright center of the Copernican universe: some dude. What the Bechdel test is signalling is that a vast majority of popular movies limit women to the status of objects, plot devices or symbols. Even the sympathetic ugly friend graced with an ounce of emotional complexity is merely a man mirror. She’s there so he can see himself or so we can see him in a different light, so we can say, “oh look, he’s not a completely self-involved, vapid POS; he has an unattractive female friend.” (Except that he is, and honestly, we’d be upset if he hooked up with the fat chick.) The takeaway is that only men can be real people. Women are accessories, tools, and only have value in terms of what they mean for men. The very fabric of society depends on it (Levi-Strauss is just reading the rules). What the Bechdel test exposes is that in representations of society, women cannot exceed their roles as objects and cannot, cannot, cannot be allowed to form their own bonds…unless they’re over men.

If movies are meant to reflect the world, this is a sorry state. Worse still, we seem to be admitting more and more that our artistic representations of society shape society as much as they reflect it. This opens a line for interpreting popular movies as actively cultivating this state of affairs. These days, we’re starting to take this whole representation thing seriously, and suddenly an obscure cultural reference from a lesbian comic book that’s older than I am is now on everyone’s lips. My problem (I always have a problem. Blogs are glorified rant spaces; don’t be shocked) is that nowadays, everyone is giving themselves a pat on the back for passing Bechdel. But, it’s not a litmus test. It’s not a box you check. If two women have a five second exchange about a sword — even if one of them is the hero — this does not mean it’s a feminist film (Admittedly, The Force Awakens may not pass feminist muster for me, but The Last Jedi is giving me a new hope). There are feminist leaning movies that don’t pass the Bechdel test — Run Lola Run, Shrek — and there are wildly unfeminist movies that do — How to Lose a Guy in Ten Days, Weird Science.

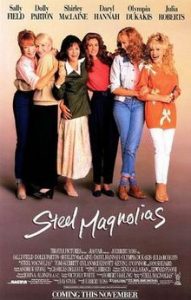

I’ve begun to feel lately that some movies are shoehorning in Bechdel test passing gestures because they think the appearance of representation and actual representation are the same thing. Crazy Rich Asians is still Cinderella even if a breastless girl has a conversation with a princess about microloans for women. This is how I came to the question of what this test is really demanding with its incredibly low bar of we just wanted to be in the movie and have a fighting chance at enough psychological depth to be a plausible human and not an electron to a dick-shaped nucleus. This made me ask if passing the Bechdel test is about feminism or about something else, and further, what’s the requirement I’m imagining for something to be feminist. Steel Magnolias passes the Bechdel test with flying colors. There are six female characters, with names, who constantly have conversations that are not about men. The women develop as people, as do their relationships with one another. For good measure, even the audience’s understanding of these women and their relationships evolves. But, for me, I find it difficult to call this movie feminist, even when I remember that it came out in 1989. It’s normative to the point that Julia Roberts’s character is painted as a hero for knowingly sacrificing her life so that she can produce a male heir. She tries to convince her mother to support her decision by saying that she “would rather have 30 minutes of wonderful than a lifetime of nothing special.” Life without making a baby, for women, is bleh. Bleh at best. This is not the only moment of regressive and confining goals for women, but it’s certainly my favorite…well maybe when Dolly Parton makes fun of a wedding guest for dancing with a younger man and wearing a dress so tight that her butt looks like “two pigs fighting under a blanket.” Shut up Dolly. At least she’s making something happen under her blanket.

This is how I came to the question of what this test is really demanding with its incredibly low bar of we just wanted to be in the movie and have a fighting chance at enough psychological depth to be a plausible human and not an electron to a dick-shaped nucleus. This made me ask if passing the Bechdel test is about feminism or about something else, and further, what’s the requirement I’m imagining for something to be feminist. Steel Magnolias passes the Bechdel test with flying colors. There are six female characters, with names, who constantly have conversations that are not about men. The women develop as people, as do their relationships with one another. For good measure, even the audience’s understanding of these women and their relationships evolves. But, for me, I find it difficult to call this movie feminist, even when I remember that it came out in 1989. It’s normative to the point that Julia Roberts’s character is painted as a hero for knowingly sacrificing her life so that she can produce a male heir. She tries to convince her mother to support her decision by saying that she “would rather have 30 minutes of wonderful than a lifetime of nothing special.” Life without making a baby, for women, is bleh. Bleh at best. This is not the only moment of regressive and confining goals for women, but it’s certainly my favorite…well maybe when Dolly Parton makes fun of a wedding guest for dancing with a younger man and wearing a dress so tight that her butt looks like “two pigs fighting under a blanket.” Shut up Dolly. At least she’s making something happen under her blanket.

But, then I have to think again about the feminist demand the Bechdel test is making and the perhaps narrow view I have of what feminists look like. Bechdel is asking that women be represented in a real way and that they not be isolated from one another.  Steel Magnolias is doing that and more. The women have free reign to express themselves and make their own choices, even if damaging patriarchal structures are tacitly informing those choices and the women show zero recognition of that fact. It shows problems that women really confront and allows them to think, feel and act ambivalently. This makes the movie feminist. Furthermore, the women are unapologetic about their choices and their behaviors. Bechdel demands complex heroes, not idealized heroines (we all know how that turns out in things like Wonder Woman). Steel Magnolias does that and more. So, who’s being narrow, rigid and prescriptive now. Looks like me.

Steel Magnolias is doing that and more. The women have free reign to express themselves and make their own choices, even if damaging patriarchal structures are tacitly informing those choices and the women show zero recognition of that fact. It shows problems that women really confront and allows them to think, feel and act ambivalently. This makes the movie feminist. Furthermore, the women are unapologetic about their choices and their behaviors. Bechdel demands complex heroes, not idealized heroines (we all know how that turns out in things like Wonder Woman). Steel Magnolias does that and more. So, who’s being narrow, rigid and prescriptive now. Looks like me.