I’m addicted to a premise. (Admittedly, I’m addicted to several, otherwise saying no to romcoms and space odysseys about boys with daddy issues would be much easier). Here it is: an absurdly hot girl (who’s also absurdly unaware of how hot she is) finds she has super powers, which enter her into a world full of magic and more absurdly hot people.

Typically, how she came to have these powers begins as a mystery, which is revealed over the course of several episodes or the whole movie and at some point constitutes, along with whatever will-they/won’t-they, the only real reason you’re even still watching this drivel. This revelation usually elucidates hot-girl’s life purpose (how being intimately connected to why in any context), and by the end of the show run, she will be called upon as the only one able to save our world, their world, all worlds. Thank God for this waify bitch and her magical hands, back flips, gun, hoo-ha or what-have-you.

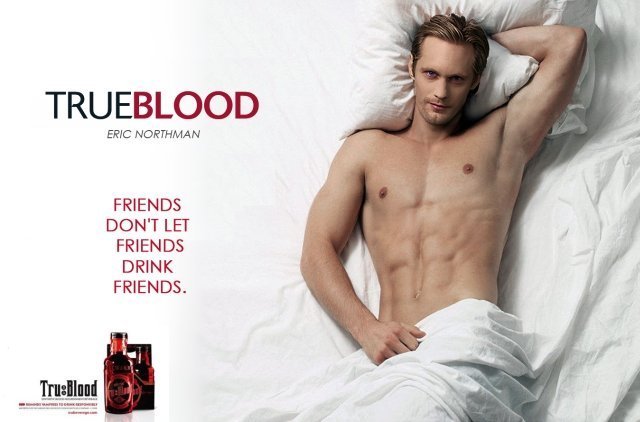

During my initial tirade on this, to which a one-eyed teddy bear acted as my enthralled audience, I could think of at least eight TV shows and movies predicated on this premise that I have watched in their entirety at least twice. I recommend each, even though Rotten Tomatoes gave two of the movies 27% and 13% respectively and more than one of the TV series at some point becomes actively terrible. They are: Jupiter Ascending (2015), Mortal Instruments (2013), Lost Girl (2010-2016), Haven (2010-2015), True Blood (2008-2014), Twilight (2008, 2009, 2010, 2012), Wynonna Earp (2016-) and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1992, 1996-2003). Their powers, in order: reincarnation and a bank account; demon fighting and extreme tattooing; healing and an irresistible poonani; immunity to other people’s wacko problems; mind reading and delicious blood; not having her mind read and nothing else (because Bella is basically a useless placeholder whose strength is manifest as blankness); ability to wield a powerful gun (not an innuendo, but really an innuendo); and vampire-related prophetic dreaming plus superhuman senses, durability, strength, reflexes, fighting ability and resilience. So, I bring to these lady badasses the eternal questions of litfuck: Why do I watch this and what am I unwittingly buying into when I do?

In part, I watch these things for the same reason we watch any fantasy. I put myself in the place of the character and feel like I too, another regular gal, could wake up one morning with awesome abilities coupled with flawless skin. Additionally, for the duration of my watching, I am one of these women, and one (all, read: all) of her hopelessly and singularly smitten suitors is in love with me. Cue the lineup of lanky, high-cheekboned protector-types, including wolf- boy (Kris Holden-Ried, Lost Girl), dog-man (Channing Tatum, Jupiter Ascending ), angsty and dead (David Boreanaz, Buffy), angsty with a death wish (Jamie Campbell Bower, Mortal Instruments), and mustache ride (Tim Rozon, Wynonna Earp). I’m a badass with a purpose and a boyfriend I don’t need but get to have anyway. Sex, direction, ability and salon-perfect hair. If your real life’s got you down, then fret not; you’re destined for cooler, sexier things.

Though I’m into the very empowering depiction of inordinately capable female protagonists who rock socks and get shit done, I do wonder how else these fictions might be read. In sitting back to consider, I find in these stories a strange sublimation of the trope of the witch. Witches, until their more recent revamp in things like Harry Potter, Charmed, and Practical Magic (oh, pretend you don’t remember Practical Magic), traditionally manifest qualities that scare us (us=men). They are aberrant in their gender expression: too old or twisted to bear children (the witch in Hansel and Gretel), too ugly to want to bear children with (Macbeth’s Weird Sisters), too large to be feminine (a la the White Witch in Chronicles of Narnia), too sexual to remain passive (Circe of Odyssey fame). Passivity and power are precisely the issues. Witches know things they shouldn’t and wield that intelligence with dexterity and influence. Morgan le Fay is most harrowing as a beautiful woman who aims to subvert the honorable King Arthur. That women have power and what those powers are constitute threats because they leverage ladies into positions in which they are actors not receivers, subjects rather than objects. The ends to which those powers are and might be used makes them scary. Their purpose seems deviant, and, just as why and how are linked, so too must their origins be perverse. Hence, the women trapped by the mentality of medieval Europe and early modern witch trials clearly derived their abilities from the devil.

The women featured in the examples of the premise I just can’t get enough of are not, per se, witches, but they do have mysterious powers that make them agents in their own lives to such an extent that they actually don’t need men. In fact, the men need them. This is all commensurate with a rash of more feminist fiction in the mainstream that I’m ecstatic to see, but I still don’t know how to read the explanations of the origins and purposes of these women’s extra-human capabilities. I see these explanations as the narrative’s apologia for the woman having powers that she shouldn’t. There must be some reason, some defense, for why a character that we root for has powers that are not human, that in fact make her monstrous, possibly demonic. Yes, times have changed, so it’s possible to classify a witchy-woman as a “good guy” without representing some great transgression to our current notions of right and wrong. But, the trope of the woman with supernatural abilities is old, and the one we borrow from now when we read or write Sabrina the Teenage Witch or Lost Girl will still show its relation to the roots it grew from.

In order to make monstrosity non-threatening, we must give it a reason, one that supports our worldview by echoing it or by standing as its evil, vincible contrast. In these shows and movies, our badass bitches possess their powers as a result of birthright, blood and destiny. Their purposes are to defeat demons (so therefore are not of demonic origin) or to serve as arbiter-cum-barrier between worlds. (Except for Bella Swan, whose purpose as far as I can tell is to act as an empty, silent shell of a human being so that her creepy boyfriend can get some peace and quiet from constantly hearing people who think. And maybe Sookie Stackhouse, who does refuse to sit in the corner and watch but for the most part is just lunch. Sexy lunch, but still lunch.)

The latter of these categories, which places our female wizard-gladiators at increasingly porous and blurry boundaries, has them doing the hard work of standing between. This is not only an innovative path for considering gender roles but for framing realities of being in the world. They do not clarify what should and should not be by reinforcing their dividing line but occupy a place that is both double and non-existent. Postmodernism loves this because it paves the way for entirely new logics, but it’s not so conducive to asserting good and bad, acceptable and unnatural. The former explanation bizarrely places a girl with preternatural abilities to wield a stake, a gun, a wand (not all the women act through phallic appendages, I promise) in the position of sole, benevolent savior, the only one capable of saving everyone through love and self-sacrifice. Remind of you of anything, Jesus? The idea that there is more to the world than what meets the eye, that some things defy explanation and do not owe us one, is central to religious faith, and there is plenty of fiction that tells the story of Christ’s magic through a chosen-one protagonist. (Right, Neo?)So, to what strand of readings do these lady badasses belong? And if main characters are always a sort of surrogate self, who am I getting off on thinking I am? I don’t know, but I believe that Buffy can save us all.