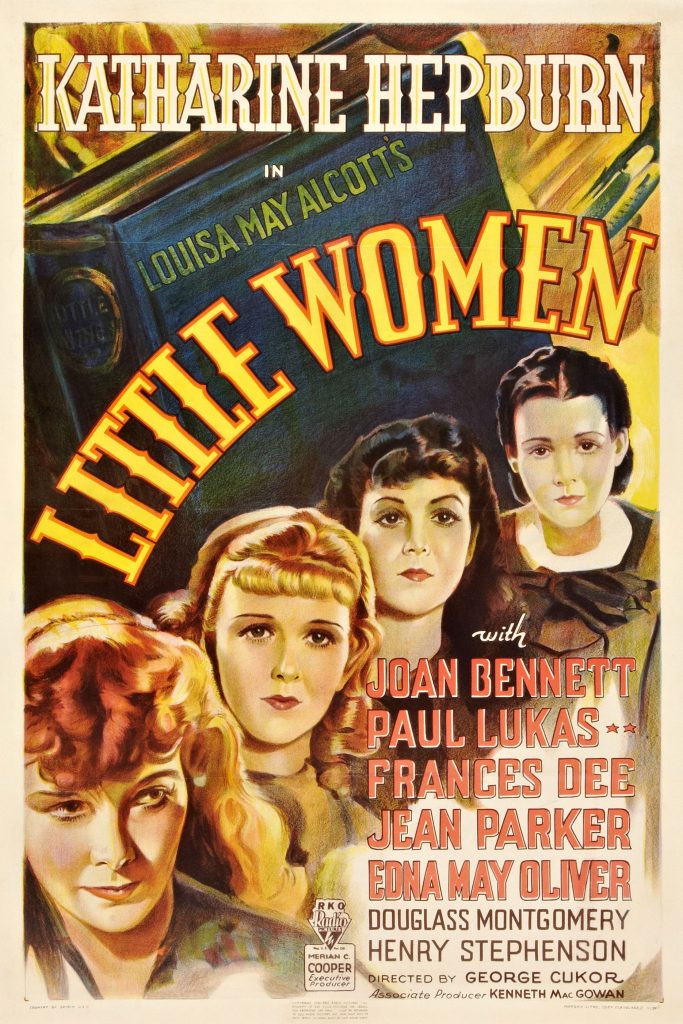

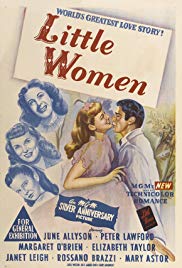

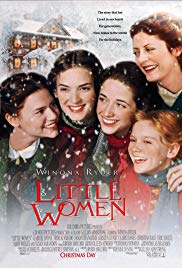

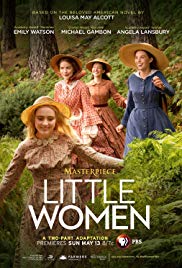

Warning: The Following Contains Spoilers for Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. But honestly, how did you not already know how it ended? Louisa May Alcott’s book has been made into a movie 1,933 times. No 1,949 times. Well actually 1,994 times. Ok, at least 2,017 times. I can’t tell if they just do it again for every era’s it girl, or if there’s some menstruating god above who, based on a moon-cycle I can’t decipher, has need of a cry and a pint of Hagen-Daaz at specific intervals.

At any rate, fair warnings issued. Let’s start with the end.

Rom-coms have this build near the end of a movie, a pitching up towards the apex where the lovers move past their pride and misunderstandings, declare their love and kiss. Think of the moment right before Richard Gere takes a limo ride and climbs a fire escape. When Harry decides to race through the streets of Manhattan to meet Sally before midnight. When that little kid from Love Actually convinces Liam Neeson to take him to the airport, so he can confess his love to the girl he’s crushing on, fool Heathrow security and sway me to believe that TSA is useless.

Even when we feel how contrived it is, we give in to it. If rom-coms are a kind of porn (which they are; the movie Don Jon captures this well), then the scene I’m talking about is the last bit of foreplay. In Gerwig’s Little Women, Jo (Saoirse Ronan) stands at the door with Friedrich (Louis Garrel) as he talks about moving West and out of her life forever. The shot is tight to their faces and as soon as he walks out, it cuts to a wide angle where you see the whole family has watched this interaction. The audience to this adorable bout of emotional dysfunction then does the movie equivalent of chanting “Jo and Friedrich sitting in a tree, K-I-S-S-I-N-G.” They explain to our reluctant and lovelorn protagonist that she’s “finally in love” and prepare her to run after him, to the train station, in the rain. If the rom-com tropes weren’t enough to signal where to situate this type of scene in your movie viewing lexicon, the building strings should seal the deal.

But, holy Gloria Steinem, how can this adaptation be ending this way? This Little Women that put the line, “I’d rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe” from Alcott’s personal journals into fictional Jo’s mouth. This Little Women that might finally win Saoirse Ronan an Oscar for a gut wrenching cry for women’s intellectual ambition. Why is Greta Gerwig doing this to her feminist literary hero? I thought for a moment that I saw soft focus around Ronan’s face. Am I supposed to mine this exaggeration for an intellectual comment about Little Women being the OG rom-com? Trust me, I love a good rom-com ending. I routinely get lost in a procrastination spiral that is just me watching supercuts of romantic movie kisses. (Careful, this is a YouTube hole). But, this is not the frame of mind meant for Gerwig’s 21st century Little Women: shut down your critical brain and turn on your ovaries; it’s time for a palatable level of feminism with a marriageable ending.

Worry not, however. Just as Jo’s sisters pull her giddily up the stairs to change into an outfit more suitable to the mad dash towards love as it slips away in the night, we cut to Jo, sitting calmly in her publisher’s office negotiating endings and book rights. The back and forth that ensues is between an author and her publisher, literary integrity and prevailing tastes, the rom-com ending and one born of a kind of feminism that cannot abide such confining fluff as a woman’s only happy climax. The scenes then alternate between the space where books are made (at the publisher, through the voice/hand of the author) and the space where their plots occur (in the telling, in the mind of the audience). We have Jo in the rain with inexplicably French Friedrich Bhaer presaging a blissful life of matrimony and motherhood. We have Jo at the office demanding her 6.5% of the profits and watching, as though through the windows of a maternity ward, her baby book birthed from the presses.

You could read this as a wink and a nod that the real ending is the shot that closes the film, the one where Jo gives a satisfied smile upon seeing what her intellectual labor and tireless self-advocacy has accomplished. But, let me tell you, the movie has two, simultaneous endings. You’re getting your dopamine-oxytocin rom-com hit from Jo March’s hands acting proxy for yours, filling Friedrich’s very attractive and poetically empty ones. And, you’re enjoying the self-righteous feeling that comes from smugly undermining the lesser-minded viewer’s desire for an ending that you know is complete and utter malarkey. Gerwig is having her cake and eating it too. So are we. But, what’s the point of cake if you’re not going to eat it?

My question is how, narratively and cinematically, does the movie manage to carry off two endings that have been set as opposing? It does so by creating a second narrative frame. We jump out to a meta-level. Until this moment, the movie has had a single plot space. Though chronologically reordered, the story you’re watching is the one told within Little Women. Normally, creating a second narrative frame in the last ten minutes of a movie is a sloppy move. Such a structural conceit, even when it’s a surprise twist, should be wrought from the beginning, at the very least, its seeds planted. (It’s been done well many times. A few examples). But Gerwig puts this in there, really out of nowhere, and we don’t bat an eyelash. Why isn’t this jarring?

The answers are several. One, we’re well coached in multiple, particularly meta, story frames. Consider, by 1987, Mel Brooks is able to spoof on it. This is an extreme example, but we’ve yet to tire of frames in frames in frames. (Extra points for frames that know they’re frames.) Two, Little Women has been adapted so many times that even if we haven’t seen other versions, the possibility of multiple alternatives conditions our approach to this telling of the story. And three, my favorite and clearly on the hearts and minds of the makers, is our obsession with authors, especially Louisa May Alcott. In the 1960s, several literary critics (including Barthes and Foucault) took issue with our tendency to read an author into their text or treat the author as a key for deciphering it. Elevated criticism be damned, we do it nonetheless, particularly when the work is about an author and more still when the fiction is said to closely parallel the life of the person who wrote it. The doubling or splitting of the narrative that happens at the end of Gerwig’s Little Women is like the author sitting next to us in the theater saying, “this is what really happened” or “let me explain, this is what I actually wanted.” It’s love, research and a necessary level of hubris that allow each new director/screenwriter/critic to think that they can wield the authorial key that unlocks the text.

The ending works for me. Alcott never married. Why should her Jo? But my god I love a love story. In this Little Women, I get to have all the soaring jollies of string-music infused romance to glide me into the critical feminist satisfaction of ‘the point is not the conquered man but the accomplished woman.’ It does all this without advocating our new, also damaging fantasy/standard that women must aim to have it all: a full life of the mind and an uncompromised life of the heart. (See Caroline Siede, whose analysis of the ending is similar to mine, for more on this). But from the perspective of narrative construction, it’s sloppy. Nevertheless, I rejoice in the simultaneous duality the ending achieves. F. Scott Fitzgerald once said, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Maybe we’re getting smarter. We don’t decide which ending to buy into and dismiss the other entirely. We let them exist on different planes; we let them feed one another; we get our cake and damn well eat it too.